When Innocence Suffers: The Catalyst of Transformation in Fiction

- Mike

- Sep 25, 2025

- 4 min read

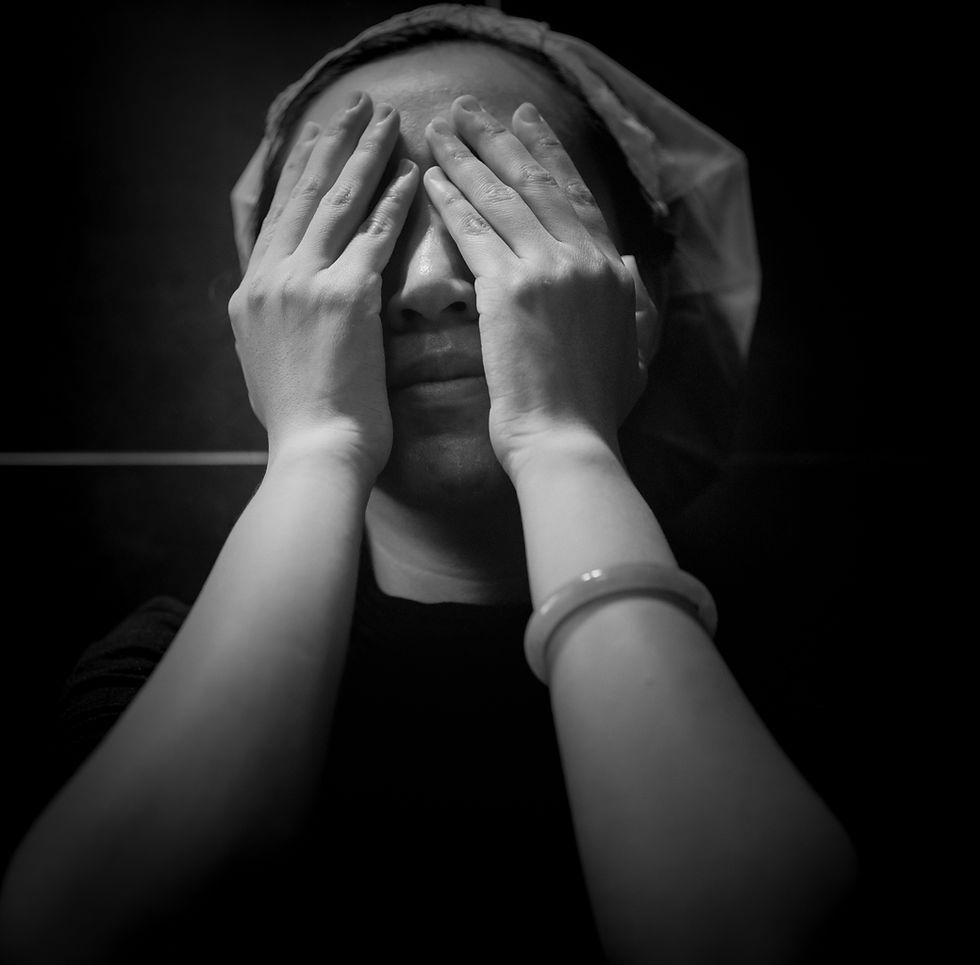

We don’t read speculative fiction to escape suffering—we read it because suffering, especially when it strikes the innocent, gives weight to hope. It raises the stakes. It carves out the emotional low point so the climb back up means something.

The question isn't why we let innocent characters suffer in fiction. The better question is: What does their suffering unlock—both in the narrative and in us, the reader?

In my stories, and the stories I most admire—Iteration, Recursion, Dark Matter, The Atlantis Gene—the loss of innocence or the pain of innocent characters often serves as a fulcrum. It's where characters shift. It's where the human experience reveals itself—not in triumph, but in what we’re willing to endure on the road there.

The Emotional Gravity of Innocence

There's a reason we flinch when a child dies, or when a character with simple, good intentions gets caught in the crossfire. We recoil. We want to intervene. That emotional friction is intentional.

In Iteration, I didn’t make Jessica suffer because she deserved it. Quite the opposite. I made her suffer because the story demanded someone who still believed in decency—someone who still showed up for others, even when it broke her—to stand in stark contrast to the characters who’ve calcified against pain. You don’t need to love blood and tragedy to understand why it matters in fiction. You just have to understand that suffering is the currency of transformation.

The Suffering is the Shift

Characters who remain untouched by pain don't evolve. They stagnate. Peng, for instance, begins the story in control—cold, intellectual, untouchable. But control is an illusion. What forces his growth isn't revelation, but loss. And it’s not even his loss—it’s Jessica’s. Seeing innocence collapse under the weight of responsibility is the thing that unsettles him. Shocks his certainty. Pulls him, against every calculated instinct, toward connection.

This is the paradox of fictional suffering: it's not meant to glorify pain. It's meant to interrupt comfort.

Suffering, particularly the undeserved kind, is a narrative accelerant. It can forge a bond between reader and character in a single paragraph. When done right, it bypasses intellectual analysis and goes straight for the throat.

It makes you feel. And that feeling creates stakes far higher than any world-ending scenario.

From Despair to Catharsis

In some of the most powerful speculative fiction I've read—and in what I try to write—innocent suffering isn’t just a breaking point. It’s a doorway.

Take Blake Crouch’s Recursion. It opens with what feels like a moment of random tragedy, a woman teetering on the edge of a rooftop, undone by memories that aren’t real—or worse, might be. That moment lands because it’s not the protagonist on the ledge—it’s an innocent bystander to time's malfunction. A life rewritten against her will.

Her suffering triggers a spiral of decisions that ripple across time and identity. And ultimately, it leads to hope. But not easily. Not quickly. That’s the point. Happy endings are earned—not because we fix everything, but because we walk through the wreckage anyway.

Earning Redemption Through Suffering

There’s an underlying tension in speculative fiction that’s hard to explain unless you live in it: the more out there the concept, the more grounded the emotional core needs to be. Time travel, neural networks, alternate timelines, alien tech—it all starts to unravel if we don’t care about the people it’s happening to.

That’s why the suffering of innocents is so crucial. It roots the abstract in the emotional. It reminds us that every grand idea has a cost.

But here’s where it gets interesting—and where I plant most of my stories: innocent suffering isn’t just tragedy. It’s an opportunity for redemption.

Think of Malcolm. Cold. Rational. Driven by loss. His arc doesn’t come full circle because he wins. It comes full circle because he realizes that survival without connection is just another form of death. And he realizes this not through science or logic, but through the fallout of Jessica’s selfless pain.

Suffering Isn’t the Point. Change Is.

The goal isn’t to write grim stories. It’s to write earned joy.

Too many narratives confuse stakes with spectacle. A thousand people die in a fiery explosion, and we feel… nothing. But a single character we love suffers unfairly, and suddenly the story sticks with us. Why?

Because stakes aren’t measured in body counts. They’re measured in what characters lose, and how they claw back meaning from it.

You want a happy ending? Earn it.

Let your characters break. Let the ones who deserve better carry the weight anyway. Then, when the light finally comes—however faint—it’ll feel real.

Final Thought

Innocence suffering isn’t just a plot device. It’s the weight that tips the scale. And when done well, it makes the ending sweeter—not because we ignored the pain, but because we honored it.

In speculative fiction, especially, we write about worlds that are strange, broken, and terrifying. But the best stories don’t leave us there. They show us that even in those shattered places, someone can choose to do good. Someone can choose to rebuild.

And sometimes, the most broken characters become the most capable of love—not in spite of their suffering, but because of it.

That’s what makes the ending matter.

Not just in fiction. In life, too.

Comments